Muscles

Muscles are groups of cells in the body that have the ability to contract and relax. There are different types of muscle, and some are controlled automatically by the autonomic nervous system. Other muscles, like the skeletal muscle that moves the arm, is controlled by the somatic or voluntary nervous system.

Jump to:

Hand Muscles

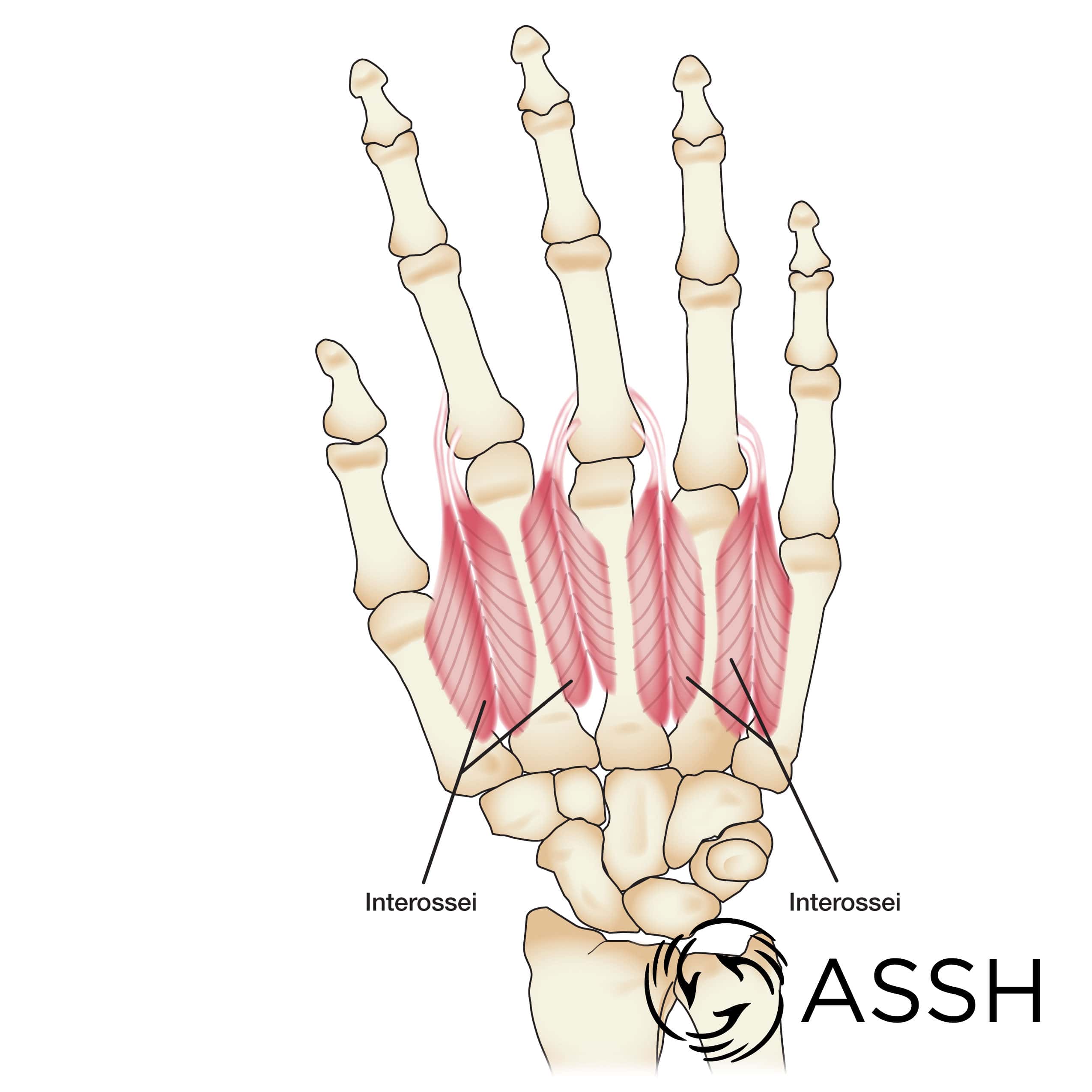

Interossei (dorsal and palmar)

Interossei (dorsal and palmar)

The interossei muscles begin between the bones of the hand. There are four dorsal and three palmar interossei muscles. While all interossei bend the MCP joints, the dorsal interossei allow us to spread our fingers away from each other. The palmar interossei pull our fingers together.

The first dorsal interosseous muscle is the largest and originates from the 1st and 2nd hand bones. It forms the contour between the thumb and index finger when looking at the top of the hand and is often the first muscle to shrink in patients with severe cubital tunnel syndrome due to damage of the ulnar nerve. In addition to pulling the index finger away from the middle finger, it also pulls the thumb towards the index finger. This action provides strength and stability when pinching.

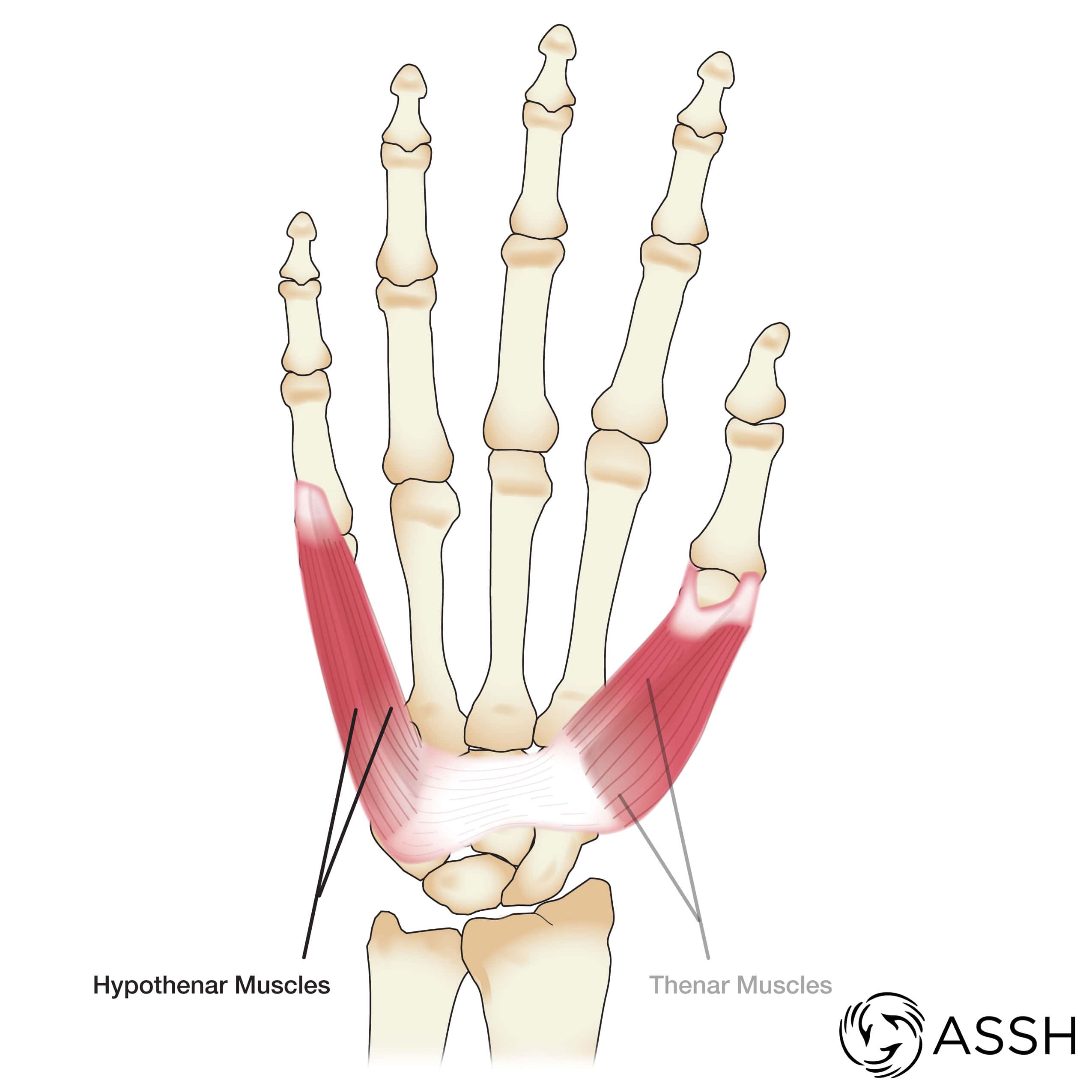

Hypothenar

Hypothenar

The hypothenar muscle group is formed by three muscles: the abductor digiti minimi, the flexor digiti minimi, and the opponens digiti minimi. They form the muscle bulk on the small finger side of the hand. The abductor allows the small finger to pull away from the ring finger. The flexor allows the small finger to bend at the MCP joint. The opponens allows us to cup our hands, bringing the small finger towards the thumb.

Thenar

The thenar muscle group is found at the base of the thumb, forming the muscle bulk on the thumb side of the hand. It is comprised of three muscles: the abductor pollicis brevis, the flexor pollicis brevis, and the opponens pollicis. The abductor pollicis brevis pulls the thumb away from the index finger, and the flexor pollicis brevis bends the thumb toward the small finger. The opponens pollicis performs one of the most important functions of the human hand: the ability to bring the thumb away from the fingers so that we can grasp objects. It helps pull the thumb away from the index finger, while rotating it, so that the tip of the thumb is opposite, or “opposes,” the tips of the other fingers. This fundamental function of the human hand is lost in severe carpal tunnel syndrome when the median nerve is damaged.

Lumbricals

Lumbricals

The main role of the lumbrical muscles is to allow the fingers to straighten, although they can also help bend the MCP joints, which are at the knuckle. The name of this muscle is derived from the Greek word for earthworm.

Thumb Muscles

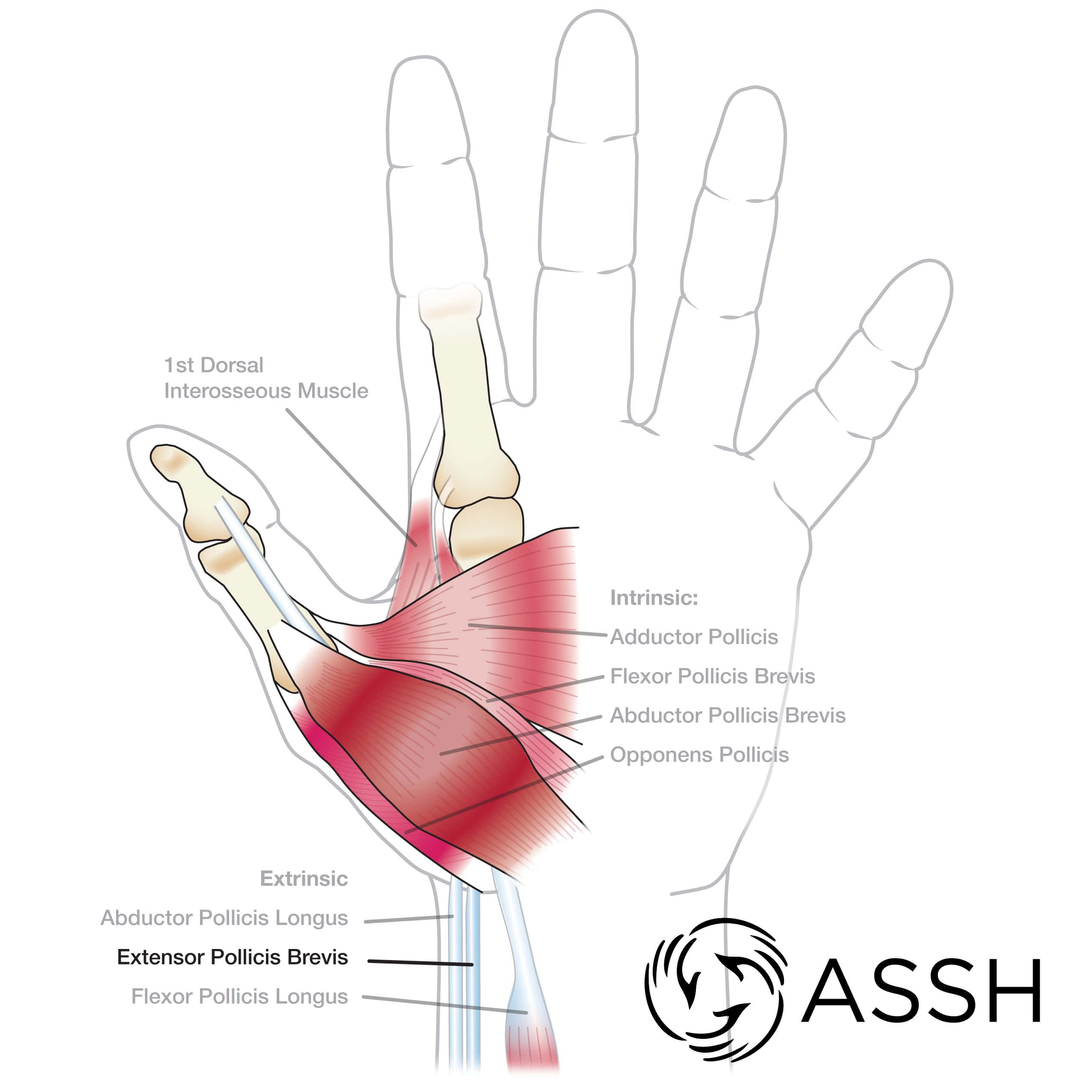

Adductor Pollicis

Adductor Pollicis

The adductor pollicis’ primary role is to provide power for pinching. It helps fill the first webspace between the thumb and index finger and weakens with severe cubital tunnel syndrome or other lesions of the ulnar nerve.

Abductor pollicis longus

The abductor pollicis longus passes through the 1st dorsal compartment of the wrist. Tendonitis is common in the 1st dorsal compartment, commonly called De Quervain Syndrome or “Mommy thumb,” due to its incidence in mothers of young children.

Elbow Muscles

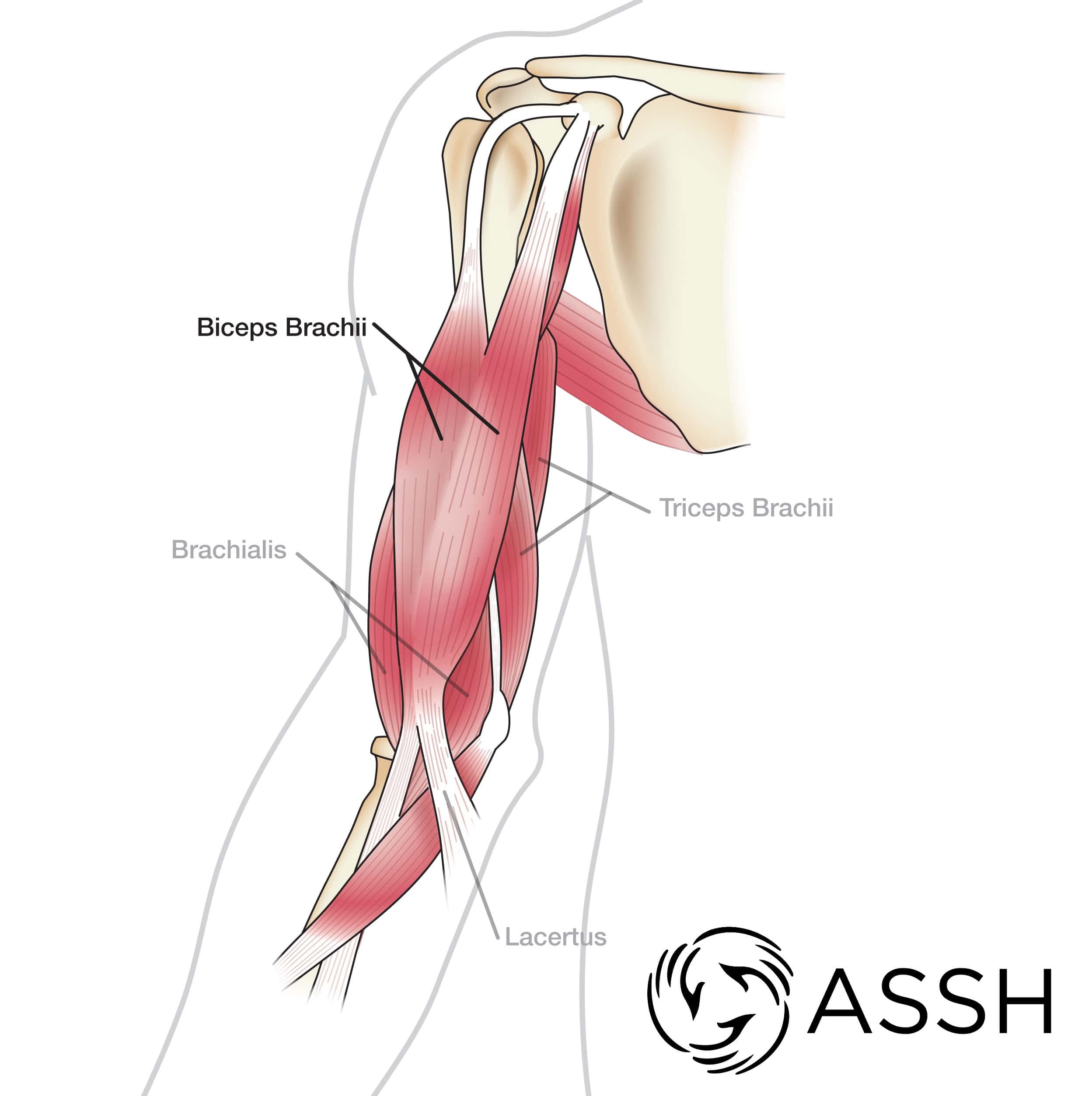

Biceps

Biceps

The biceps is named for its two heads – short and long. The biceps is the main supinator of the forearm (which helps us rotate the palm up and down), and helps the brachialis and brachioradialis in bending the elbow. The biceps is prone to injury, particularly the tendon of the long head and the distal tendon which inserts into the radius. Rupture of the tendon of the long head allows the biceps muscle to sink lower in the arm, creating a “Popeye” deformity. Fortunately, after the initial pain goes away, there is little loss of strength due to the continued attachment of the short head. If the distal tendon ruptures, though, the muscle no longer has any attachment below the elbow, and there may be an approximate 30% loss of elbow strength, and 40% loss of supination strength.

Brachialis

The brachialis is a large, deep muscle in the front of the arm. It lies beneath the biceps muscle and attaches onto the coronoid process of the ulna, just below the elbow joint. The brachialis is a strong flexor of the elbow (allowing it to bend).

Triceps

The three-headed triceps muscle is the only muscle in the back of the arm. The triceps provides the important action of straightening our elbow, allowing us to push up out of a chair and throw a ball. It also stabilizes the elbow when you are forcefully supinating (think turning a screwdriver), otherwise the bending action of the biceps would be unopposed, and our elbows would bend with every twist.

Shoulder Muscles

Deltoid

Deltoid

The large muscle on the outside of the shoulder is the deltoid, named from the Latin deltoides, which means “triangular in shape.” The deltoid has three heads and originates from the front, side, and back of the shoulder from the clavicle, acromion, and scapular spine, respectively. The three heads form a joined tendon that attaches to a prominence on the outside of humerus bone (deltoid tuberosity). Each head can work independently, as well as together. When the arm is at the side, the front (anterior) head of the muscle moves the arm forward. The middle head moves the arm sideways, away from the body, and the back (posterior) head moves the arm backwards. The deltoid is active in most shoulder motions, helping to stabilize the shoulder during carrying, lifting, and even walking.

Infraspinatus

The infraspinatous also arises from the back of the scapula, but from the area below the scapular spine. Because of its position more behind the shoulder joint, it works to primarily externally rotate the arm, as when cocking the arm back to throw, or to put your hand behind your head. It is also frequently involved in rotator cuff tears, most commonly when the supraspinatous is also torn, creating a large tear and greater loss of function.

Supraspinatus

The supraspinatous is one of the four rotator cuff muscles. The rotator cuff is the group of tendons of the subscapularis, supraspinatous, infraspinatous, and teres minor which attach around the head of the humerus encircling it like a cuff. The supraspinatous arises from the upper part of the back surface of the shoulder blade (scapula) above the scapular spine. It attaches to the greater tuberosity of the humerus, forming the upper border of the rotator cuff. It works to bring the arm away from the body, and to stabilize the head of the humerus into the socket of the shoulder (glenoid). Degeneration and tearing of the supraspinatous is a common cause of shoulder pain, and it is the most common rotator cuff muscle to tear from its attachment.

Teres major

The teres major arises from the tip at the bottom of the shoulder blade, below the teres minor. It crosses the back of the shoulder and attaches to the upper humeral shaft, below the head. Like the teres minor, it helps bring the arm into the body, but unlike the teres minor, it is an internal (not external) rotator of the arm. Fortunately, the teres major is very rarely injured, but it remains an important muscle to keep strengthened for proper shoulder function.

Teres minor

The teres minor sits just below the infraspinatous in the back of the shoulder. It originates from the outer edge of the shoulder blade, then travels up to the lowest portion of the greater tuberosity. Like the infraspinatous, its primary action is to externally rotate the shoulder, but due to its lower position, it also helps pull the arm into the body.

Subscapularis

Subscapularis

The subscapularis is the only rotator cuff muscle in the front of the shoulder. It arises from the front surface of the shoulder blade, and attaches to the lessor tuberosity of the humerus. Its main action is to rotate the arm towards the body (internal rotation), as when putting your hand on your stomach. It is the largest and strongest rotator cuff muscle, and, in addition to its importance during throwing and racquet sports, it is an important stabilizer of the shoulder joint.

Latissimus dorsi

Aptly named, the latissimus (meaning “broadest” in latin) dorsi is a large, thin muscle that arises from the lower spine, ribcage, and tip of the shoulder blade. It forms the back wall of our armpit (axilla) on the way to its attachment to the humerus. The “lat” provides power for pull-ups and the rowing motion, bringing the arm backwards, and in towards the body. Despite its strength and importance, the latissimus is frequently used as a muscle transfer, or as a flap to cover a large wound or for breast reconstruction. Fortunately, most patients are able to compensate for its loss within 9 to 12 months.

Pectoralis Major

The pectoralis major is a large chest muscle with two heads. The clavicular head arises from the collar bone (clavicle), while the sternocostal head arises from the breastbone (sternum) and rib cage. The two heads join to form a flat tendon which attaches to the upper humeral shaft, just in front of the latissimus tendon. It provides power for many arm actions, including flexion (as when throwing a ball side-armed), internal rotation (arm-wrestling), and adduction (pulling the arm in towards the body). Injuring the pectoralis major usually requires a substantial force, typically occurring in weight-lifters during a bench press when fatiguing and losing control of the weights.

Coracobrachialis

The third major muscle in the front of the arm is the coracobrachialis. Named for its origin and insertion, it arises from the coracoid process of the shoulder blade and inserts into the humerus. Its main role is to flex the shoulder, bringing the arm forward, as happens during normal walking. It also pulls the arm in towards the body (adduction), working in conjunction with the deltoid to stabilize the arm while reaching.

Wrist and Forearm Muscles

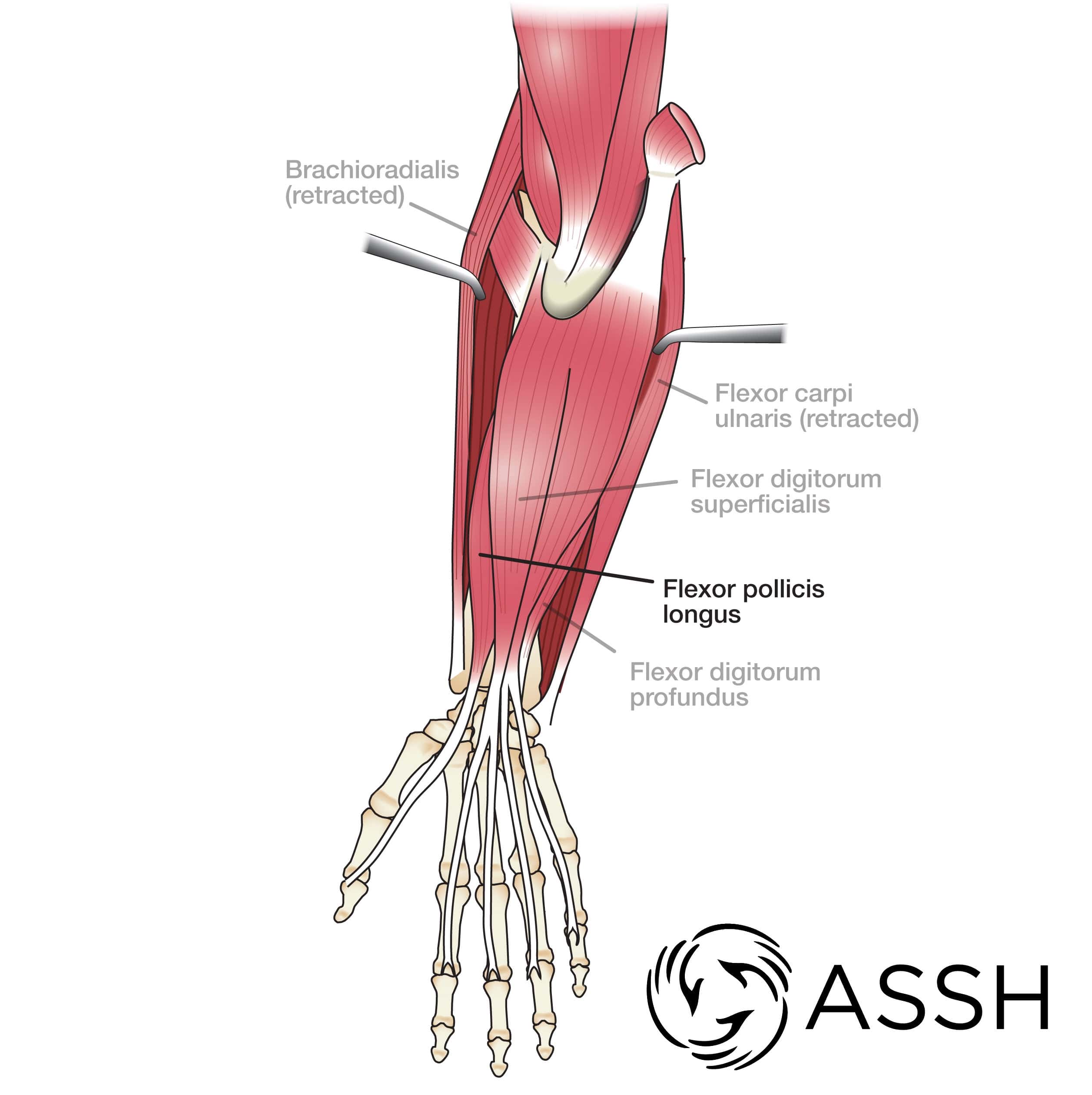

Flexor Pollicis Longus

Flexor Pollicis Longus

Arising from the mid-forearm from the radial shaft, the flexor pollicis longus allows us to bend the tip of our thumb. It is the ninth tendon to pass through the carpal tunnel on its way to the thumb.

Flexor Digitorum Profundus

Located deep in the forearm, the flexor digitorum profundus arises from the ulna and interosseous membrane. From the muscle, four tendons emerge which pass through the carpal tunnel and insert into the tips of the index, middle, ring, and small fingers. Its primary action is to bend these fingers, and due to its insertion past the last joint of the finger, it is able to bend all three finger joints. Unlike the FDS, there is a common muscle belly for the middle, ring, and small fingers, typically preventing us from bending the tip of one of these fingers without the others bending as well. There is a separate muscle belly for the index finger FDP, though, contributing to its independence.

Flexor Digitorum Superficialis

The flexor digitorum superficialis arises from the medial epicondyle (an elbow bone) between the palmaris longus and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscles. In the forearm, the FDS has four independent muscle bellies from which four tendons arise. After crossing the wrist, they pass through the carpal tunnel, then spread out to the index, middle, ring, and small fingers. The primary function of the FDS is to bend the middle joint of each finger (except the thumb). The independence of each finger’s FDS contributes to our hand’s skill in performing tasks, such as using chopsticks.

Flexor Carpi Ulnaris

The final muscle to arise from the medial epicondyle (an elbow muscle) is the flexor carpi ulnaris. It also has two heads, with the larger head arising from the ulna beginning just below the elbow and continuing over two-thirds the length of the forearm. It then becomes a tendon, crosses the wrist, and attaches at the pisiform bone at the base of the palm. This large muscle is built for power, bending and deviating the wrist away from the thumb. This is the second part of the dart thrower’s motion and also useful while using a hammer.

Brachioradialis

Arising from the outside of the elbow is the brachioradialis (BR). The BR inserts into the end of the radius bone, just below the wrist joint (the distal radius), in line with the thumb. The forearm is in neutral position when the thumb is up, small finger towards the ground. In this position, the BR is a pure flexor of the elbow. If the palm is facing towards the ground, the BR can twist the forearm until the thumb is in the up position again (neutral). When the palm is facing up, the BR twists the forearm back to the neutral position.

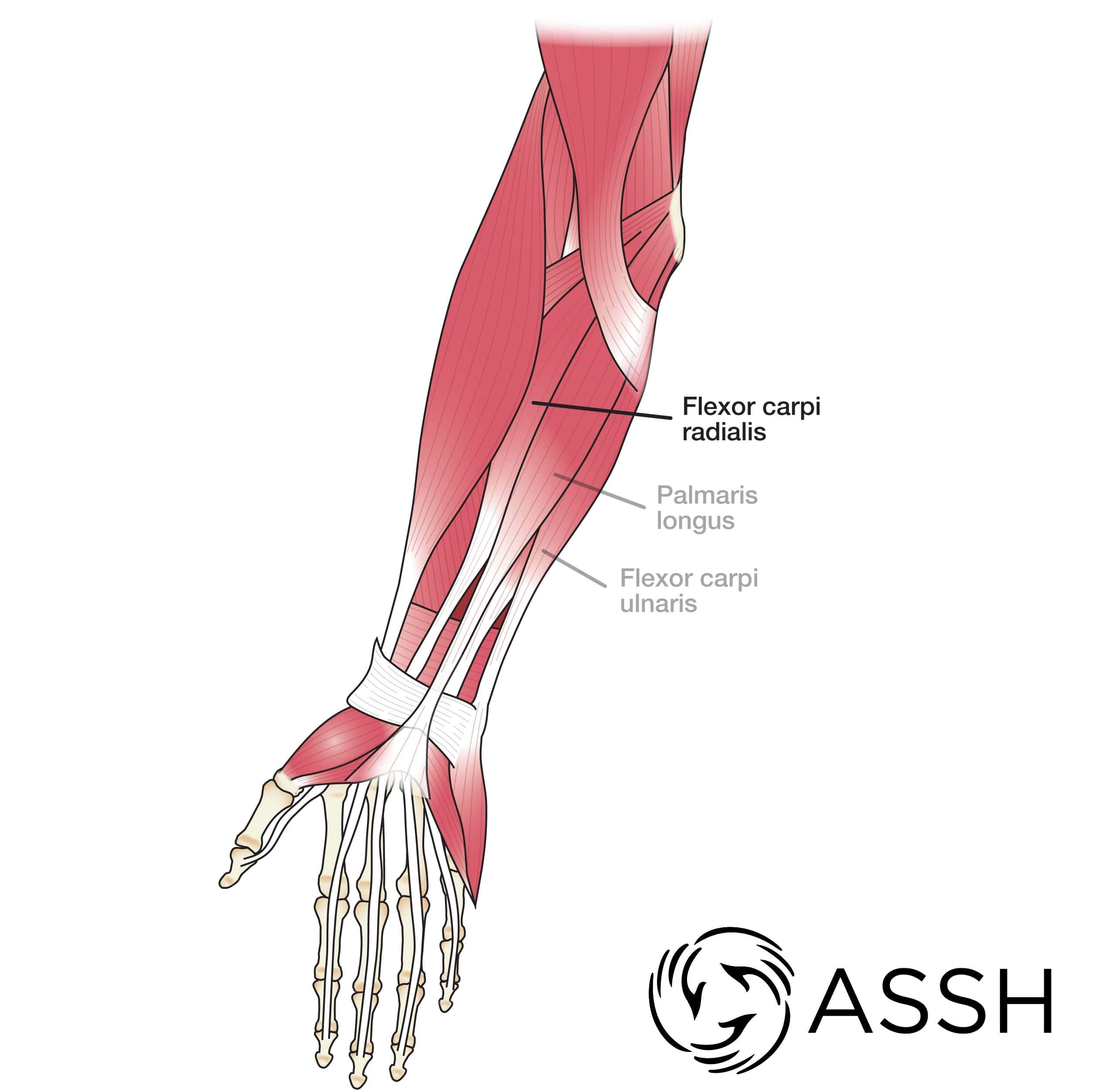

Flexor Carpi Radialis

Flexor Carpi Radialis

The flexor carpi radialis arises adjacent to the pronator teres (an elbow muscle), crosses the elbow and wrist, and attaches to the base of the second hand bone. Its primary role is to bend the wrist, and it can help to move the wrist towards the thumb. At the wrist, the FCR tendon passes through a tunnel and is prone to tendonitis or even rupturing. Fortunately, we can live without the function of the FCR; therefore it is a commonly used tendon for reconstruction or as a tendon transfer.

Palmaris Longus

Next to the FCR arises the palmaris longus muscle. This muscle, with a long tendon, travels down the forearm to the center of the wrist and palm, where it attaches to the palmar aponeurosis (a fibrous tissue layer between the thenar and hypothenar muscles). It functions as a flexor of the wrist, and like the FCR is expendable. In fact, it is absent in one or both arms in 12%-25% of people. When present, it is frequently used as a source for tendon graft, where it is removed and used to rebuild a ligament or more important tendon. It is also a commonly used tendon transfer.

Extensor Pollicis Brevis

The main action of this muscle is to straighten the thumb at its middle joint. If the EPB becomes separated from the APL tendon by a subsheath, it creates a narrower tunnel for the EPB to pass through. Patients who develop de Quervain’s Syndrome and have a subsheath may be more likely to need surgery.

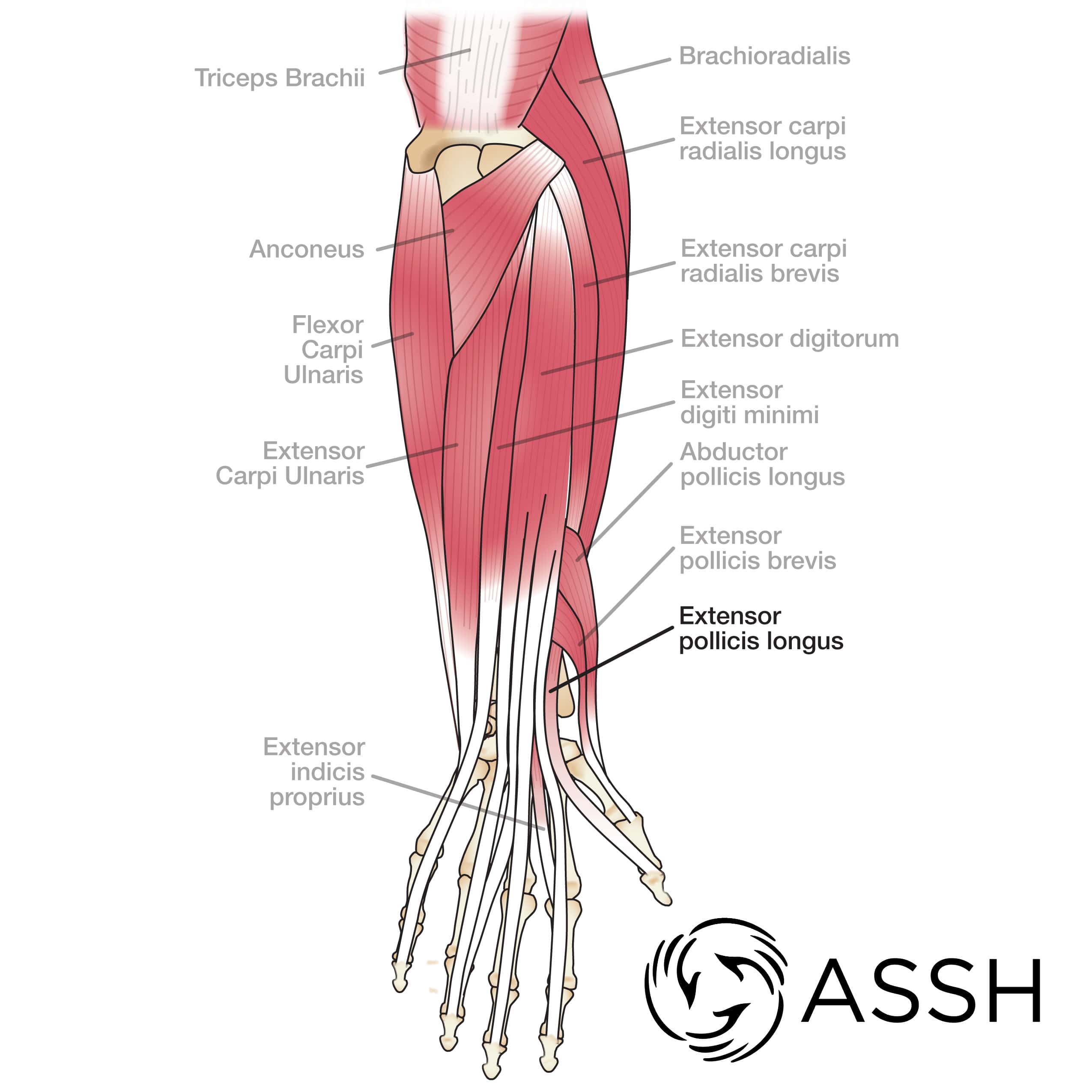

Extensor pollicis longus

Extensor pollicis longus

The extensor pollicis longus attaches at the thumb and acts primarily to straighten the tip of the thumb. This important action allows us to give a “thumbs up” or bring the thumb into a hitchhiker position. Tendonitis of the EPL is unusual, however it is prone to rupture in its compartment. Most typically, this originates from non-displaced wrist fractures (breaks) or inflammatory arthritis.

Extensor carpi radialis brevis

The extensor carpi radialis brevis arises just above the elbow. It crosses both the elbow and wrist joints before inserting onto the third hand bone. Its main function is to straighten the wrist and stabilize the wrist during power grasp. Inflammation of the ECRB can occur in the forearm at the intersection where the APL and EPB muscles cross the ECRB and ECRL tendons. This is known as intersection syndrome. The ECRB is also often partially responsible for pain on the outside of the elbow, also known as tennis elbow or lateral epicondylitis. When the origin of the ECRB is damaged from overuse, aging, or injury, the pain of tennis elbow occurs. Fortunately, this condition is usually self-limiting.

Extensor carpi radialis longus

The extensor carpi radialis longus arises just above the ECRB muscle on the outside of the elbow and attaches to the 2nd hand bone. Along with the ECRB, its primary function is to straighten and stabilize the wrist. It also pulls the wrist into radial deviation. This is the first part of the motion required to throw a dart, as the wrist cocks back. It is also implicated, along with the ECRB, in intersection syndrome – a tendonitis of these tendons at the site where the APL and EPB cross over them.

Extensor carpi ulnaris

The last (6th) of the dorsal compartments houses the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon. Arising from the lateral epicondyle, an elbow bone, it attaches to the 5th hand bone after passing over the ulna bone. Its primary function is to straighten and stabilize the wrist, and it also provides the ability to move the wrist away from the thumb. The ECU is anchored to the ulna by the ECU subsheath which can be injured during golf and racquet sports. When the subsheath ruptures, the ECU tendon will snap around the ulna in certain wrist positions causing pain.

Extensor digitorum communis

The extensor digitorum communis provides the ability to straighten the index, middle, ring, and small fingers. It separates into four separate tendons. Through each tendon’s attachment, the EDC primarily extends the MCP joints (at the knuckle) but also contributes to extension of the PIP and DIP joints in the fingers.

Extensor digiti minimi

The small finger does not receive an EDC tendon in at least 50% of people. The extensor digiti minimi fills that gap, providing two tendons to the small finger 84% of the time.

Extensor indicis proprius

The extensor indicis proprius attaches to the extensor expansion over the MCP joint of the index finger (at the knuckle). It provides us the ability to independently straighten the index finger, as it has no juncture connecting it to other extensor tendons.

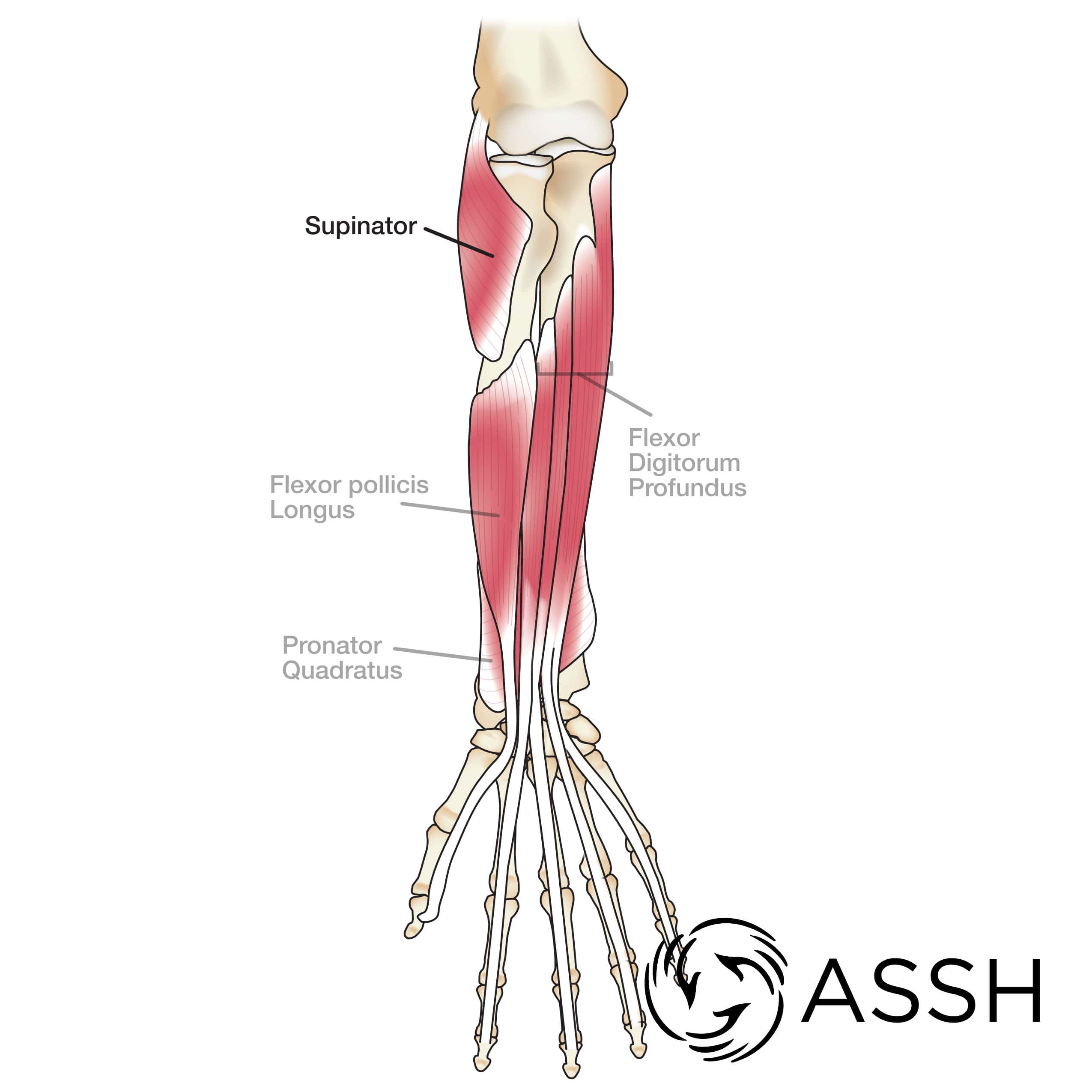

Supinator

Supinator

Supination of the forearm is the act of twisting the forearm into the palm up position. The supinator is located just below the elbow. The supinator provides about one half the power of the biceps muscle for supination. The supinator is also important as a location where the radial nerve can be entrapped. The radial nerve divides just prior to the supinator with the branch supplying muscles travelling through the supinator muscle between its two heads. The nerve can be pinched either at the entrance or exit point of the muscle, causing forearm pain or weakness of finger and thumb muscles.

Pronator quadratus

The pronator quadratus muscle is found in the forearm just below the wrist. It has two heads, arising from the ulna and inserting onto the radius. With the pronator teres, the pronator quadratus allows us to twist our forearm into the palm-down position (pronation). The pronator quadratus is the main pronator of the forearm, especially as the elbow becomes more flexed, weakening the contribution of the pronator teres.

Pronator Teres

This muscle attaches to the radius in the mid-forearm and acts to twist the forearm into the palm down position (known as pronation). It can be involved in golfer’s elbow (medial epicondylitis) which causes pain at the site of bending. It can also cause irritation or compression of the median nerve, which passes between the two heads of the muscle.